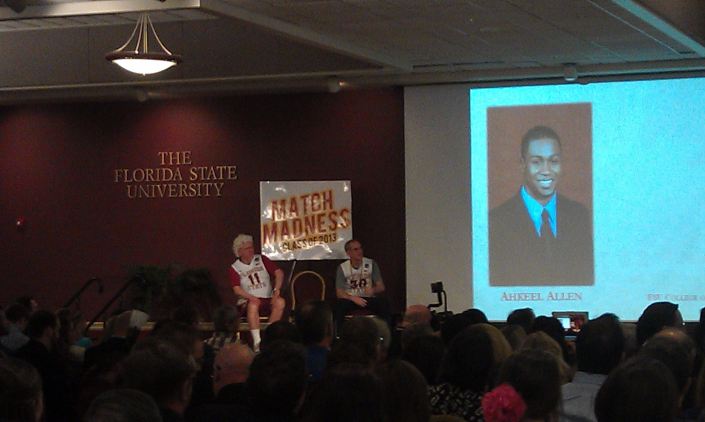

My wife is a pediatrician. In mid-March 2013 we experienced “match day,” the day where senior medical students match to a specialty-hospital pair for their residencies. For a moment stroll with me down memory lane: All the soon-to-be doctors were dressed up with family and friends in tow. There was so much chatter, excitement, hugs —the whole place was electric. The ballroom was decorated in a “Match Madness” theme and medical school faculty dawned basketball and referee uniforms with whistles and headbands. Each senior medical student was handed an envelope with their match location and speciality inside. And though I wanted to tear the thing open we were told not to open it until the appointed time.

When the envelopes were opened it is difficult to communicate the emotion. So much time invested in medical school and so many great and terrible experiences in the process of becoming a doctor. And, the hope after visiting so many different residencies, that you would get your preferred choice. We were very happy when we found out we were headed to Greenville, SC. The program there is stellar with committed attendings and a 100 percent pass rate on the pediatric boards for the last several years. That’s better than any pediatric residency east of the Mississippi.

So how did “match day” come about? In 1952 John Stalknaker and F. J. Mullen designed the National Residency Matching Program (NRMP) to alleviate problems in the labor market for physicians. The problem was,

“…competition for scarce medical students forced hospitals to offer residencies (internships) increasingly early, sometimes several years before graduation. Matches were made before the students could produce evidence of their qualifications, and even before they knew which branch of medicine they would like to practice. When an offer was rejected, it was often too late to make offers to other candidates …”

The NRMP required both students (hospitals) to submit a ranking of their most desired hospitals (students). Then an algorithim would match students and hospitals. In 1984, economist Al Roth showed that this algorithim was strategy-proof and produced “stable” matches. A match is stable if nobody perceives that a swap between residents and hospitals would be mutually beneficial. Later Al Roth would make modifications to the NRMP to accommodate married doctors. This is part of the work that eventually won Al Roth the 2012 Nobel Prize, “for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design.”

Speaking of Al Roth, he also happens to be a Senior Scientific Advisor at MobLab. In 2016, after a long day of job interviews and climbing hills in San Francisco I sat down for dinner at Le Colonial with the folks at MobLab. When he sat down at the table I was starstruck. Not knowing what to say, I leaned over and shook his hand, “Thank you, Professor Roth. My wife and I are very happy with where she matched.” He laughed and smiled. He was kind and gracious in conversation and told me, “call me Al.” That is a dinner I won’t forget.

It pleases me greatly to announce that soon MobLab will be releasing its KR Matching Game (the KR stands for Kagel and Roth and refers to this paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics). In this paper Kagel and Roth study the decentralized matching system that “unraveled” (with early matches and miscoordinations) as well as centralized systems like the NRMP. Their experiments provided a greater degree of confidence that what they had observed in a handful of cases were robust.

In our new game we will allow our instructors to run students through different matching markets to allow students to experience market unraveling and the different solutions to that problem. Keep a look out for the game in the “Market” tab in your instructor console.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the problem of matching is ubiquitous and far beyond NRMP. As Al Roth states in his excellent Freakonomics interview,

“Matching markets are markets where money, prices don’t do all the work. And some of the markets I’ve studied, we don’t let prices do any of the work. And I like to think of matching markets as markets where you can’t just choose what you want even if you can afford it — you also have to be chosen. So job markets are like that; getting into college is like that. Those things cost money, but money doesn’t decide who gets into Stanford. Stanford doesn’t raise the tuition until supply equals demand and just enough freshmen want to come to fill the seats. Stanford is expensive but it’s cheap enough that a lot of people would like to come to Stanford, and so Stanford has this whole other set of market institutions. Applications and admissions and you can’t just come to Stanford, you have to be admitted.”

Thinking through how different institutions or “rules of the game” affect market outcomes is really important. Behind all that math there is a human component. My wife and I are almost certainly happier with our outcome than we would have been before 1952.

Check out our KR Matching game and the rest of our game catalog! Interested in learning more? Schedule a meeting with someone from our team to get started!