A few years ago my wife and I were on a date at Jasmines, our favorite Sushi restaurant in Tallahassee. From 5-7pm there were two-for-one beers. We both ordered a beer thinking we would split the two-for-one. The food came and we were talking and having a great time. The time flew by. It was already 6:30 or so and we planned to see a movie at 7:05 at a theater about 15 minutes away. Then, I looked down at my beer and, realizing I slowly drank the first beer throughout the meal, said, “We have another beer coming to us. I need to get the waitress to bring it quickly.” Then, with perfect timing, my wife gave a wry smile and said, “You’re just falling victim to the sunk cost fallacy.” What?!? My own wife using my economic karate against me! Even economists fall victim to the sunk cost fallacy.

What is an example of sunk cost fallacy? In this case the sunk cost (cost already incurred) was the payment for the beer. Individuals then make the next decision based on what nets them the highest gain. In this case, attempting to shotgun a beer before the movie is not a high benefit option for me. The other option was not taking advantage of the two-for-one. I should have evaluated those two options on their own merits without consideration of what I had already paid. The fact that I had some compulsion that, “I paid for it, therefore I need to drink it,” is where the fallacy came in play.

Sunk cost fallacies are also present in major business decisions where managers might continue to throw good money after bad in an R&D effort because, “We’ve already invested so much.” At MobLab we have a host of “Behavioral Economics Templates” to help illuminate concepts like the sunk cost fallacy. Running the “Mental Accounting: Sunk Cost Fallacy” survey some students will receive question A while others receive question B:

Once the answers have been submitted you can discuss the differences in response rates between the two options. In both cases you have lost something worth $20 of monetary value and now must make a decision to purchase the ticket. However, the number of people purchasing the ticket will be substantially higher with Option A than Option B. Why? Because we set up “mental accounts” where we separate economic activities into different categories. In this case, the relevant mental account might be “concert attendance.” When you have lost your $20 ticket that loss accrues to your mental account for “concert attendance” and you feel less inclined to increase the costs incurred in that account. However, the lost twenty dollars was not yet part of the mental account for “concert attendance” so the purchase of a ticket would not be viewed as an additional cost in that mental account.

In addition to the sunk cost fallacy we have a number of other interesting behavioral economics experiments in our arsenal including questions related to availability bias, anchoring bias, questions related to probability assessments, and more. With MobLab, you can put your students into mini behavioral experiments to show them their own cognitive biases and start meaningful discussions about a variety of behavioral economics topics. Check out our games and surveys to see how MobLab fits into your class.

Want to learn more? Get in touch with our team! We are eager to set it up for your class.

What is an example of sunk cost fallacy? In this case the sunk cost (cost already incurred) was the payment for the beer. Individuals then make the next decision based on what nets them the highest gain. In this case, attempting to shotgun a beer before the movie is not a high benefit option for me. The other option was not taking advantage of the two-for-one. I should have evaluated those two options on their own merits without consideration of what I had already paid. The fact that I had some compulsion that, “I paid for it, therefore I need to drink it,” is where the fallacy came in play.

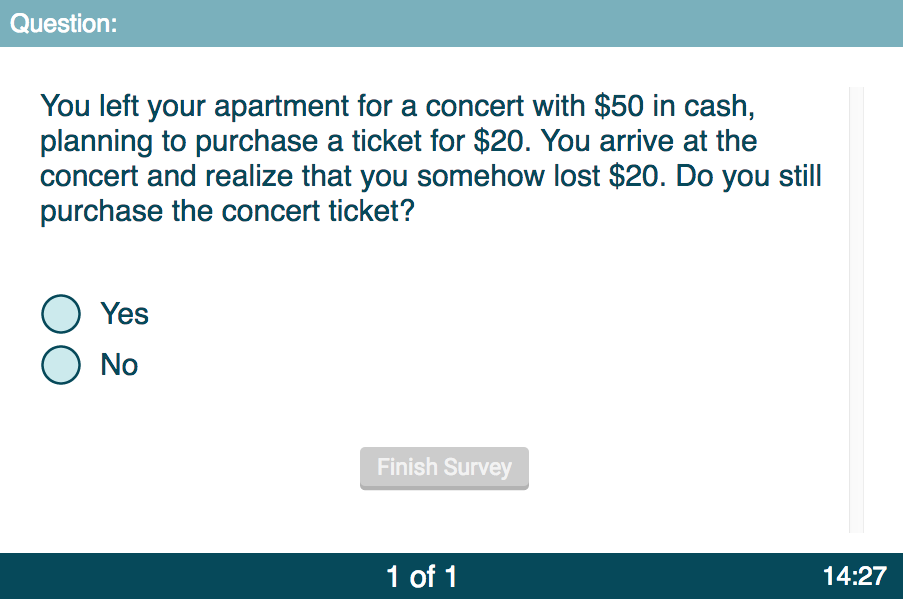

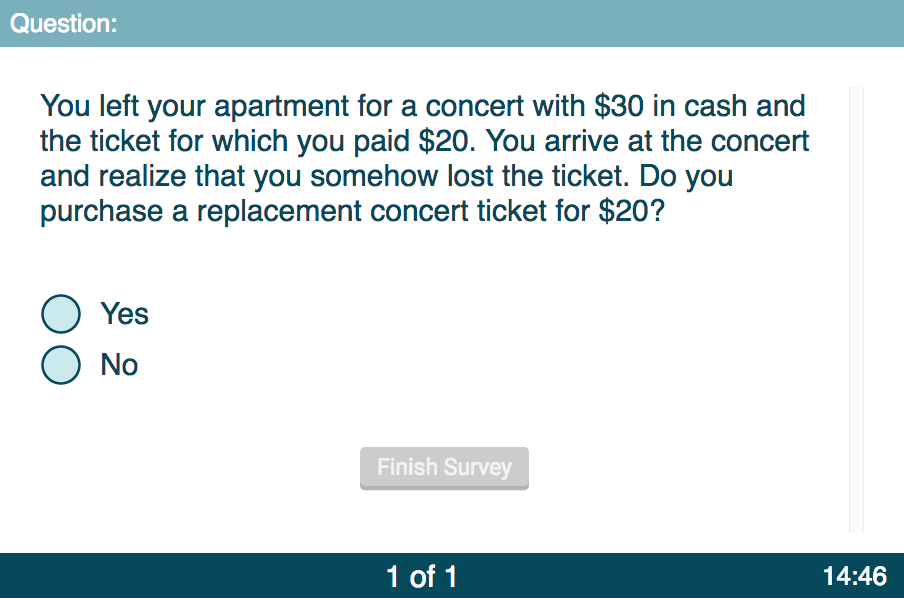

Sunk cost fallacies are also present in major business decisions where managers might continue to throw good money after bad in an R&D effort because, “We’ve already invested so much.” At MobLab we have a host of “Behavioral Economics Templates” to help illuminate concepts like the sunk cost fallacy. Running the “Mental Accounting: Sunk Cost Fallacy” survey some students will receive question A while others receive question B:

A. You left your apartment for a concert with $50 in cash, planning to purchase a ticket for $20. You arrive at the concert and realize that you somehow lost $20. Do you still purchase the concert ticket?

Yes/No

B. You left your apartment for a concert with $30 in cash and the ticket for which you paid $20. You arrive at the concert and realize that you somehow lost the ticket. Do you purchase a replacement concert ticket for $20? Yes/No

Once the answers have been submitted you can discuss the differences in response rates between the two options. In both cases you have lost something worth $20 of monetary value and now must make a decision to purchase the ticket. However, the number of people purchasing the ticket will be substantially higher with Option A than Option B. Why? Because we set up “mental accounts” where we separate economic activities into different categories. In this case, the relevant mental account might be “concert attendance.” When you have lost your $20 ticket that loss accrues to your mental account for “concert attendance” and you feel less inclined to increase the costs incurred in that account. However, the lost twenty dollars was not yet part of the mental account for “concert attendance” so the purchase of a ticket would not be viewed as an additional cost in that mental account.

In addition to the sunk cost fallacy we have a number of other interesting behavioral economics experiments in our arsenal including questions related to availability bias, anchoring bias, questions related to probability assessments, and more. With MobLab, you can put your students into mini behavioral experiments to show them their own cognitive biases and start meaningful discussions about a variety of behavioral economics topics. Check out our games and surveys to see how MobLab fits into your class.

Want to learn more? Get in touch with our team! We are eager to set it up for your class.